The Seventy Year History and Copyright Authorship of “Wagon Wheel”

Background

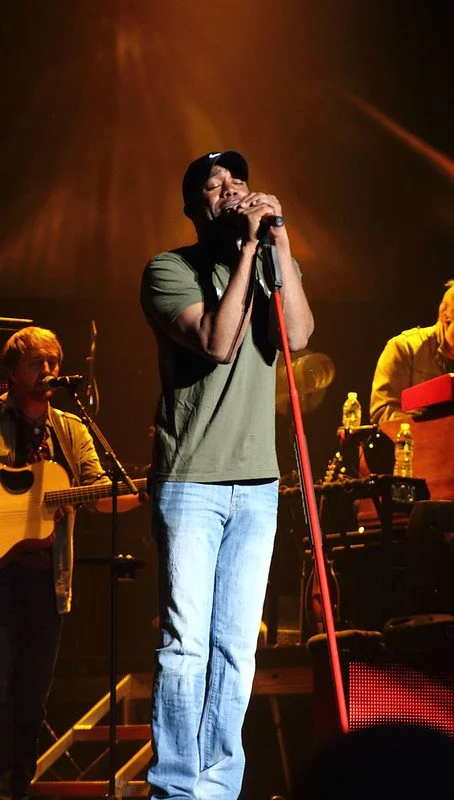

In 2022, Darius Rucker’s version of “Wagon Wheel” earned diamond status, the Recording Industry Association of America's (RIAA) highest certification, indicating 10 million units of the song have been streamed or sold. [1]. Released in 2013 off his fourth studio album True Believers, the song was a massive sensation critically and commercially. [2]. Rucker won the Grammy for Best Country Solo Performance for “Wagon Wheel,” becoming only the second Black American to win the award. [3]. While Rucker may have performed the most popular (and in the author’s humble opinion, the best) version of “Wagon Wheel,” he did not actually write it. So, who did?

On its face the answer seems simple: U.S. Copyright Registration PA0001233553 lists two authors for the words and music of “Wagon Wheel”: Bob Dylan and Jay Ketcham Secor (“Ketch Secor”). [4]. However, at the time Bob Dylan and Ketch Secor filed the copyright application, Dylan made a confession his cowriter: he did not write possibly the most famous line in the song, “rock me mama.” [5]. Dylan admitted that blues artist Arthur Crudup wrote it. [6].

Now, Arthur Crudup did, in fact, write and release a song titled “Rock Me Mama,” however Arthur Crudup said he didn’t come up “rock me mama” either! [7]. Crudup claimed another blues artist named Big Bill Broonzy did. [8]. On top of that, three other artists may have also contributed to the famous lyric as well. Curtis Jones’s blues hit “Roll Me Mama” came out before Arthur Crudup’s “Rock Me Mama.” [9]. Also, Sonny Terry’s song “Rock Me Mama” and Melvin “Lil’ Son” Jackson’s highly influential song, “Rockin’ & Rollin’” could have also served as sources of lyrical origin. [10].

The lyrical history of “Wagon Wheel” raises an important question in the context of copyright law: why isn’t Arthur Crudup, Big Bill Broonzy, or whoever came up with the line “rock me mama” (which is repeated sixteen times throughout the song) listed as a co-author along with Bob Dylan and Keth Scor?

Let’s take a step back in time and examine the seventy-year history of “Wagon Wheel,” including the many artists who contributed to its diamond-certified lyrics, and learn about the copyright authorship of this legendary song.

Act I: Big Bill Broonzy and Arthur Crudup (Chicago, IL, 1940s)

Big Bill Broonzy once told a crowd at a Copenhagen jazz club “my name is William Lee Conley Broonzy.” [11]. His name was an amalgamation of various family names: Wiliam, one of his father’s brothers, Lee, the husband of his paternal aunt, and Conley, the husband of his maternal aunt (although it remains unclear where “Broonzy” came from). [12].

Born in rural Jefferson County Arkansas on June 26, 1903, as the eighth of ten children to Frank Bradley and Mittie Belcher, Big Bill Broonzy’s full legal name was (most likely) Lee Conley Bradley. [13]. While internationally known as a guitarist, Bradley’s first instrument was a cornstalk fiddle, which he fashioned together from cornstalks in the cotton fields he worked. [14].

In the early 1920s, Bradley boarded the Illinois Central Railroad and moved to Chicago. [15]. To make a living, he worked at the Pullman Company, where he climbed the ranks to earn the highly coveted position of a sleeping-car porter. [16]. For a couple of years, Bradley worked at the Pullman Company, busked and played house parties in Chicago while he learned to master the guitar. [17].

Between 1925 and 1926, Bradley began recording his first songs with Paramount Records, which is where he earned his lifelong nickname “Big Bill.” [18]. According to Bradley, when he was checking in with the secretary at the recording studio he told her his name was “William Lee Conley Broonzy,” to which the exasperated secretary replied “[f]or Christ’s sake, we can’t get all that on the label.” [19]. The secretary began calling Bradley “Big Boy” then eventually “Big Bill,” and the nickname stuck. [20]. In the summer of 1928, Bradley’s first records were available for purchase through Paramount Records. [21].

Bradley recorded over two hundred songs from the 1930s to the 1940s. [22]. One song recorded in 1940, “Rockin’ Chair Blues” contains the lyrics “rock me, baby” and “rock me, darling”:

Rock me, baby now

Rock me slow

Take your time, baby, rock me one time just before you go

Now you rock me, darling

Now rock me, baby

Now rock me, baby, one time before you go

[23].

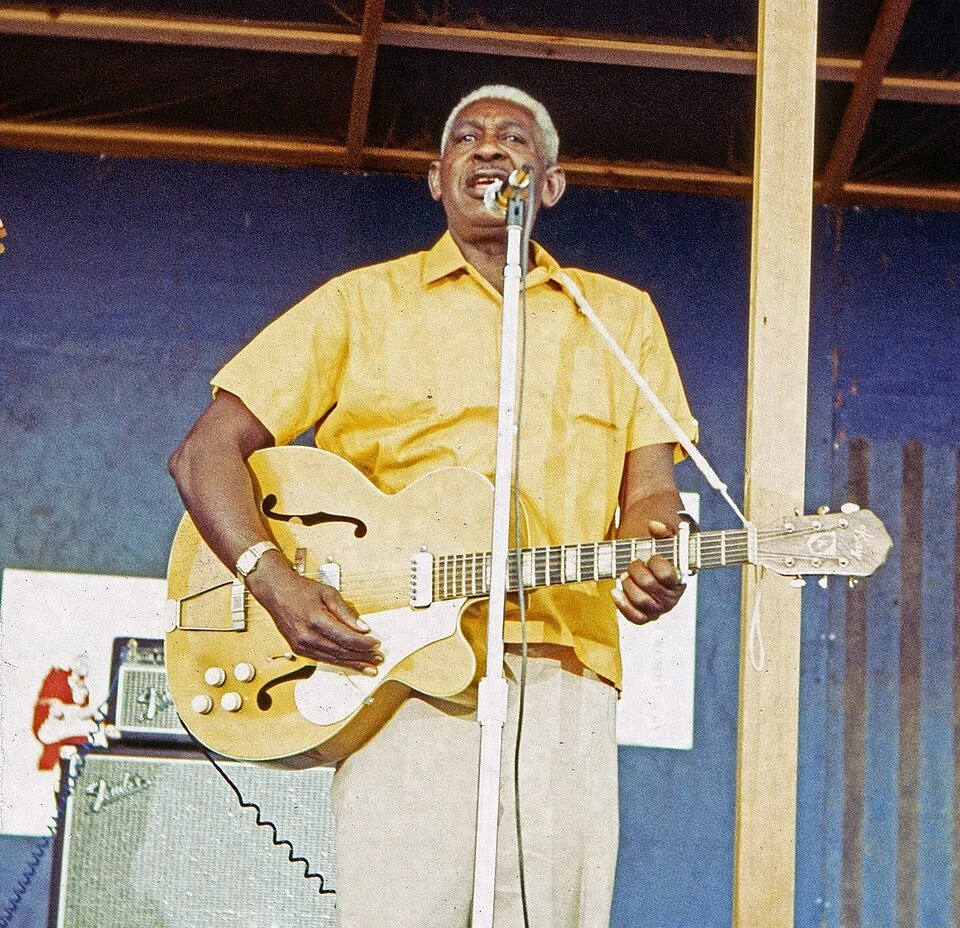

Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, another popular blues musician, was born in Forest, Mississippi in 1905. [24]. Arthur began singing the blues at just 10 years old. [25].

In the mid to late 1930s, Crudup taught himself how to play the guitar. [26]. During this time, he played parties and nightclubs throughout the Mississippi Delta. [27]. However, in 1940, like many aspiring black blues musicians, Crudup left for Chicago for better fortune. [28]. In Chicago, Crudup camped out in a crate at the 39th Street “L” station at Pershing Road and State Street, busking blues music for tips and drinks from passersby. [29].

In 1941, an agent for Bluebird Records named Lester Melrose saw Crudup on a street corner in Chicago and, impressed with what he saw, asked Crudup to play a gig. [30]. The gig in question was a house party hosted by Tampa Red, a popular blues musician who recently moved from Georgia to Chicago. [31]. The party was well-attended by other well-known blues artists, including Lonnie Johnson, Lil Green, and…

…Big Bill Broonzy! [32].

Whatever nerves Crudup might have had playing in front of industry names that night didn’t show. Shortly after the gig, Lester Melrose signed him to Bluebird Records and Crudup released his first record, “If I Get Lucky,” in 1941. [33]. In 1945, Crudup released “Rock Me Mamma,” which was based on Big Bill Broonzy’s song “Rockin’ Chair Blues,” recorded just five years earlier. [34]. “Rock Me Mama,” while very similar lyrically to “Rockin’ Chair Blues,” replaced “baby” and “darling” with “mama”:

Rock me, mama, rock me slow

Rock me one time, lord, before you go

But I want you to rock me, mama

Yeah, rock me, mama

Yes, rock me, mama

One time before you go

[35].

The story of “Wagon Wheel” then takes a nearly thirty-year hiatus, and when the story starts again, it is over 2000 miles away from Chicago and in a completely different genre of music.

Act II: Bob Dylan (Burbank, California, 1970s)

Bob Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, grew up in a small town in Minnesota. [36]. As a child, Zimmerman was enamored with blues and folk music, and he played in several different garage bands in high school. [37]. When he left for college, Zimmerman joined the local folk circuit and began going by Bob Dylan. [38].

While Dylan is best known as a folk musician, the “voice of a generation,” he acted as well. In 1973, he did a bit of both in a film called Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. [39]. The screenwriter, Rudy Wurlitzer, convinced Dylan to both act in a minor role and create the soundtrack for the film. [40].

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid told the story of two American folk legends: Billy the Kid, the gun-toting southern outlaw who died at the age of just 21 years old, and Pat Garreett, the U.S. marshal and Texas Ranger who hunted down bandits like Billy the Kid. [41]. Dylan produced the soundtrack over the course of three studio sessions; the first was an all-night session at CBS Discos Studio in Mexico City during the actual filming of the movie. [42]. The next two sessions were in Burbank Studios in California about a month later. [43].

During the first Burbank Studios recording session, Dylan recorded perhaps the most popular song on the Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid soundtrack: “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” [44]. After recording the soundtrack version and instrumental version of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” Dylan recorded “Final Theme,” the next song on the soundtrack. [45]. Then, suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere, Dylan started strumming his acoustic guitar and improvising a chorus that had nothing to do with the soundtrack he was trying to record:

Rock me mama like the wind and the rain,

Rock me mama like a southbound train,

Hey, mama rock me

Rock me mama like a wagon wheel,

Rock me anyway you feel,

Hey, mama rock me

[46]. Dylan sings this chorus several more times, with each iteration more and more musicians in the studio began to jump in, harmonizing, handclapping, and slapping a tambourine. [47]. However, despite recording a full-fledged chorus, Dylan did not finish the song during the session, nor did he pick it up later. [48]. Instead, he simply continued on recording the Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid soundtrack, leaving the song unfinished and unnamed. [49]. This unnamed, unfinished song, which was approximately 37 seconds long, was later released on a bootleg recording named “Rock Me Mama.” [53].

The story takes a twenty-year pause and story restarts in Harrison, Virginia, 2,500 plus miles away from Burbank Studios.

Act III: Old Crow Medicine Show (Harrison, Virginia – 1990s)

In the 1990s, Ketch Secor met his future bandmate Chris “Critter” Fuqua in middle school in Harrison, Viginia, and they’ve been playing music together since. [51]. Secor said that, as kids, he and Fuqua were busking on street corners and picking up any gig within driving distance. [52].

Fuqua and Secor listened to a lot of Bob Dylan in their youth. [53]. During their junior year, Fuqua played Secor the bootleg recording of “Rock me Mama,” which Secor described as the kind of song “that stays with you because you’ve heard it in a coffee shop or some cute girl was singing it on a street corner with a dog on a hemp leash when you were 14.” [54].

After hearing the bootleg recording, the then 17-year-old Secor “had the audacity” (his words) to finish an unfinished Bob Dylan song; he wrote three verses around Dylan’s chorus and thus “Wagon Wheel” was born. [55]. Secor’s verses transform the lonely chorus into an odyssey, describing the narrator’s arduous journey from New England to Tennessee to get home to his girl, perhaps inspired by Dylan’s line rock me, mama, like a southbound train. [56].

Interestingly and wholly unrelated to the lyrical history of the song, Secor’s third verse appears to contain a geographical error:

Walking to the south out of Roanoke

I caught a trucker out of Philly had a nice long toke

But he's a headed west from the Cumberland gap

To Johnson City, Tennessee

[57]. The song describes the trucker’s route as leaving west from the Cumberland gap (a pass close to where the Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee borders meet) heading to Johnson City, Tennessee. [58]. However, Johnson City is actually east of the Cumberland gap, not west. [59]. Although, it is possible that Secor meant “west” in name only instead of direction; one possible driving route from the Cumberland gap to Johnson City is to travel east on U.S. Route 11W. [60].

Regardless of whether Secor’s lyrics were youthful ignorance of geography or hyper-specific driving directions, the protagonist’s verses of hitchhiking and flower picking resonated with audiences. Secor mused that “Wagon Wheel” became so popular because “it is easy for listeners to put themselves in the hero’s role.” [61]. After penning the song, Secor, as part of the band Old Crow Medicine Show, hit the road and began performing “Wagon Wheel” across the United States. [62]. It is at this point where the story of “Wagon Wheel” comes full circle: among other big cities and small towns, Old Crow Medicine Show performed “Wagon Wheel” busking street corners in Chicago, just like Big Bill Broonzy and Arthur Crudup decades before. [63].

After traveling and performing “Wagon Wheel” for 10 years on the road, Old Crow Medicine Show finally recorded “Wagon Wheel” for their 2001 EP, and then again for their 2004 album, O.C.M.S., where it was finally released to the radio. [64].

Our story pauses for about a decade, and picks up again at a high school talent show in Charleston, South Carolina.

Act IV: Darius Rucker (Charleston, South Carolina, 2010s)

Darius Rucker was born and raised in Charleston, South Carolina. [65]. Music was present early in his life, although in a somewhat complicated way; his father, Rucker said in an interview was “never there” and his only interactions he had with him growing up was before church because his father sang in a gospel band. [66].

In 1986 as a student at the University of South Carolina at Columbia, Rucker formed a band called Hootie and the Blowfish with three of his classmates, Mark Bryan, Dean Felber, and Jim (“Soni”) Sonefeld, and began playing gigs near campus. [67]. Not too dissimilar from the early days of all of the artists in the story thus far, Hootie and the Blowfish played any gig they could get: bars, clubs, frat parties, and birthday parties, getting paid in beer and fistfuls cash and then crashing on some dorm-room floor. [68]. Everything changed in 1996 when the band released their album Cracked Rear View, which sold millions of copies, plunged them into pop stardom, and earned them two Grammy Awards, including Best New Artist. [69].

In 2008, Hootie and the Blowfish announced their hiatus, and Rucker transitioned into country music. [70]. His first and second country albums, Learn to Live and Charleston, SC 1966, were highly successful, both reached number one on the Billboard Country album chart and together produced five number one country singles. [71]. But it was in the midst of recording his third album, True Believers, where Rucker found inspiration for a new song in an unusual place.

In an interview, Rucker admitted that the first time he heard “Wagon Wheel” many years ago he “didn’t really get it.” [72]. His perception changed completely when he attended his daughter’s high school talent show and watched the faculty band perform “Wagon Wheel,” which apparently moved Rucker so much that he turned to his wife mid-song and said “I’ve got to cut this song.” [73].

The rest is history. As discussed at the beginning of this article, Rucker’s version of “Wagon Wheel” earned diamond status, earned him his third Grammy win, and went on to become one of the most beloved and popular country songs of all time.

Other Potential Contributors

While not part of the official folklore of “Wagon Wheel” according to Keth Secor, there are three songs worth mentioning that may have served as inspiration to Bob Dylan when he wrote his unfinished song “Rock Me Mama.” The first is Curtis’ Jones’s 1939 hit “Roll Me Mama,” which includes the lyrics “roll me over mama” and “wagon wheel”:

Now roll me over mama like I'm flour dough

I hate for you to leave me when It's time to go

Now roll me over

Just like I'm a wagon wheel

Cause' you'd never stop rollin' me

Baby if you knew how good you make me feel

[74]. Not only is “Roll Me Mama” worth mentioning because of its lyrical similarity to “Wagon Wheel,” but also because Bob Dylan is a known fan of Curtis Jones! In fact, the closing track on Bob Dylan’s debut album, Bob Dylan, is a cover of Jones’s song “Highway 51 Blues.” [75].

The second song worth mentioning is Sonny Terry’s song “Rock Me Mama,” which contains substantially the same lyrics as Arthur Crudup’s “Rock Me Mama” (but musically sounds very different):

Rock me mama now

Rock me slow

Rock me mama, one time before you go

Yeah, rock me darling

Yeah, rock me mama

I want you to rock me mama, one time before you go

[76]. Sonny Terry, like Arthur Crudup, probably based his song off of Big Bill Broonzy’s “Rockin’ Chair Blues.” Big Bill Broonzy (“Bradley”) and Terry likely knew each other since at least 1938; both participated in highly successful two-night concert From Spirituals to Swing, presented by John Hammond. [77]. Held on December 23 and 24, 1938 in Carnegie Hall, From Spirituals to Swing showcased Black American music and featured a number of high-profile Black musicians. [78]. Indeed, not only did Bradley and Terry likely know each other at the time “Rockin’ Chair Blues” was released in 1940, Terry was a fan of Bradley’s discography. Terry and another artist named Brownie McGhee recorded their own version of Big Bill Broonzy’s 1940 song “Key to the Highway” after its release. [79].

Finally, there is Melvin “Lil’ Son” Jackson’s 1951 song, “Rockin’ and Rollin’, which was based on Arthur Crudup’s song “Rock Me Mama,” and contains the following lyrics:

Roll me, baby, like you roll a wagon wheel

Roll me, baby, like you roll a wagon wheel

I want you to roll me, you don't know how it make me feel

I want you to rock me, rock me all night long

I want you to rock me, rock me all night long

Rock me, baby, like my back ain't got no bone

[80]. “Rockin’ and Rollin,’” notably, contains the lines “rock me” and “wagon wheel,” which would end up in Bob Dylan’s “Rock Me Mama.” [81]. Musically, the song is still classic blues (and features two very nice blues solos), but leans more folk than any of the other songs so far mentioned. [82]. The original recording of the song simply features Jackson’s voice over one acoustic guitar. [83]. While there is no certainty that Bob Dylan heard this song, “Rockin’ and Rollin’” happens to be the earliest iteration of “Rock Me Baby,” which is one of the most recorded blue songs. [84]. Given that Bob Dylan was a huge fan of blues music, it is probable he listened to “Rockin’ and Rollin’” at least once. [85].

Copyright Authorship: Why Aren’t the Other Artists Listed?

In a prior blog post, we explained that, under US copyright law, an author of a copyrightable work is one who creates an embodied expression, or authorizes another to perform the embodiment on their behalf. [86]. However, to be a co-author, two things must be true: (1) each of the authors intends that their respective contributions be part of a unitary whole, and (2) each of their respective contributions are independently copyrightable. [87].

As to the first factor, while “billing or credit” is not decisive, having the respective parties credited or billed as co-authors or co-creators is strong evidence of intent of creating a joint work. [88]. The date of completion of the work is also relevant, specifically whether the date of completion listed is inclusive of both parties’ contributions. [89]

Bob Dylan and Keth Secor, in agreeing to publish “Wagon Wheel” together and filing the copyright registration with both of them listed as co-authors, strongly suggests their intent of creating a single, unitary work. [90]. Additionally, the completion date listed on the copyright registration is 2003, after Keth Secor contributed his verses to the song, further evidencing intent of co-authorship (i.e., in contrast listing the completion date as 1973, which would only include Dylan’s contribution, not Secor’s). [91].

However, there is no evidence that Big Bill Broonzy, Arthur Crudup, Sonny Terry, Curtis Jones, or Lil’ Son Jackson intended to create a unitary work with either Bob Dylan or Keth Secor, namely because all of them had passed away before Secor wrote the verses to “Wagon Wheel” in the late 1990s. More to the point, with the exception of Sonny Terry, all had actually already passed when Bob Dylan wrote his unfinished chorus in 1973. And so, without an intent to be co-authors in creating a single work, Big Bill Broonzy, Arthur Crudup, Sonny Terry, Curtis Jones, or Lil’ Son Jackson cannot be considered a co-author to “Wagon Wheel” under US copyright law.

In a lot of ways, “Wagon Wheel” is a true folk song; its lyrics are the result of seventy plus years of American musical history, passed down from musician to musician, dating back to Big Bill Broonzy’s 1940 song “Rockin’ Chair Blues” (although, Secor claims that Big Bill Broonzy recorded an earlier iteration in 1928). [92]. “Wagon Wheel,” and its lyrical forebearers, transcended genre and race, and the lyrics themselves were passed on through remarkable means: busking on Chicago street corners, an unreleased bootleg recording of a movie soundtrack, and a non-high school performance at a high school talent show. And although Big Bill Broonzy, Arthur Crudup, Sonny Terry, Curtis Jones, or Lil’ Son Jackson do not meet the legal definition of co-authorship under copyright law does not in any way diminish their artistry or contributions to one of the most successful country songs ever made.

Endnotes

[1] LB Cantrell. “Darius Rucker Honored For Diamond Certification Of ‘Wagon Wheel,’” Music Row. Oct. 27, 2022, https://musicrow.com/2022/10/darius-rucker-honored-for-diamond-certification-of-wagon-wheel/.

[2] See Paul Grein. “Mickey Guyton, Charley Pride & More Black Artists to Receive Grammy Nods in Country Categories.” Billboard. Dec. 8, 2020, https://www.billboard.com/music/awards/black-artists-country-grammy-nominations-mickey-guyton-charley-pride-9496412/.

[3] See id.

[4] U.S. Copyright Registration PA0001233553.

[5] Amy Jacques. “Old Crow Medicine Show: Growing at the Speed of Asparagus.” relix. Nov. 26 2014, https://relix.com/articles/detail/old_crow_medicine_show_growing_at_the_speed_of_asparagus/; #238 Ketch from Old Crow Medicine Show on The Untold Story Behind “Wagon Wheel” + Bob Dylan, Bobbycast (Mar. 31, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YMK9tIZ6UEA.

[6] Jacques, supra note 2; Bobbycast, supra note 2.

[7] Jacques, supra note 2; Bobbycast, supra note 2.

[8] Jacques, supra note 2; Bobbycast, supra note 2.

[9] Curtis Jones, Roll Me Mama on Curtis Jones Vol. 2 1938-1939 (1939), https://open.spotify.com/track/6i5eMmSCPOui4QF0V8GyIV?si=1c544ff482ef499a.

[10] See Clinton Heylin, The Recording Sessions [1960-1964] 91-92 (St. Martin’s Griffin 1997); see Larry Birnbaum, Before Elvis: The Prehistory of Rock 'n' Roll 4 (Scarecrow Press 2012).

[11] Bob Reisman, I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy 7, 18 (photo. reprt. University of Chicago Press 2012) (2011).

[12] See Reisman, supra note 11 at 18.

[13] Id. at 8.

[14] Id. at 21.

[15] Id. at 44.

[16] Id. at 44-45.

[17] Id. at 45-46, 48.

[18] Id. at 49, 54.

[19] Id. at 49.

[20] Id. at 54.

[21] Id. at 49.

[22] Id. at 115.

[23] Id. at 116; Big Bill Broonzy, Rockin’ Chair Blues on Feelin’ Low Down (1940), https://open.spotify.com/track/3VNomBCOYuA9jsCSJ3Hb8A?si=39a77a046f8f40b5.

[24] See Ben Finley. “Arthur Crudup wrote the song that became Elvis’ first hit. He barely got paid.” AP News. July 2, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/arthur-crudup-elvis-presley-thats-all-right-1fc62464ce99d4a9291b7ef662f1913e.

[25] Finley, supra note 29.

[26] Finley, supra note 29; Michael E. Ross. “Recalling an unsung writerof often-sung songs.” NBC News. Feb. 29, 2004, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna4307974.

[27] Finley, supra note 29; Ross, supra note 31.

[28] See Ross, supra note 31

[29] Ross, supra note 31; see Finley, supra note 29.

[30] Finley, supra note 29.

[31] Ross supra note 31.

[32] Id.

[33] Birnbaum, supra note 10 at 4.

[34] See id.

[35] See Arthur Crudup, Rock Me Mama on Rock Me Mama (Bluebird Records 1945), https://open.spotify.com/track/2klvIQb1m0faNZ83PoFB7x?si=c4eaa8cb11e44f6c.

[36] Debra Kamin. “Bob Dylan’s life and work examined in new exhibit.” Jewish Telegraph Agency. April 13, 2016, https://www.jta.org/2016/04/13/culture/bob-dylans-life-and-work-examined-in-new-exhibit.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Peter Biskind. “Hollywood Flashback: Sam Peckinpah Put Bob Dylan Through the Wringer.” The Hollywood Reporter. Feb. 16, 2025, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/music/music-news/bob-dylan-encounter-sam-peckinpah-1236132950/.

[40] Id.

[41] See Steve Erickson. “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: Renegade’s Requiem.” The Criterion Collection. Jul. 2, 2024, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/8524-pat-garrett-and-billy-the-kid-renegade-s-requiem.

[42] Heylin, supra note 10 at 91-92.

[43] Id. at 92.

[44] Id. at 93.

[45] See Id. at 93-94.

[46] Malapersona (@Malapersona), YouTube (Nov. 16, 2009), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNTsYfjBcuQ&list=PLAkeZR_06UcTimS1xn5SoxCGdV-hKGoS4&index=1; see Heylin supra note 10 at 94.

[47] Id.; see Heylin supra note 10 at 94.

[48] Malapersona, supra note 46; see Heylin, supra note 10 at 94.

[49] See Heylin, supra note 10 at 92.

[50] See Jacques, supra note 2; see Peter Burditt. “Behind The Song: The Century-Long Lineage of Bob Dylan and Ketch Secor’s ‘Wagon Wheel.’” American Songwriter. Aug. 24, 2024, https://americansongwriter.com/behind-the-song-the-century-long-lineage-of-bob-dylan-and-ketch-secors-wagon-wheel/.

[51] See Jacques, supra note 2.

[52] See id.

[53] See Bobbycast, supra note 2.

[54] Jacques, supra note 2.

[55] See Burditt, supra note 50; see Jacques, supra note 2.

[56] See Jacques, supra note 2; see Reisman, supra note 11 at 116.

[57] Old Crow Medicine Show, Wagon Wheel on O.C.M.S. (Nettwerk 2004), https://open.spotify.com/track/5aAHai9OzUlkYPk2TJ4LLp?si=a9a5a208165247ca.

[58] Id.

[59] Driving Directions from Cumberland Gap, TN to Johnson City, TN, Google Maps, https://www.google.com/maps/ (Search starting point field for “Cumberland Gap, TN” and search destination for “Johnson City, TN”).

[60] Id.

[61] Jacques, supra note 2.

[62] See Chrissie Dickinson. “It took an Old Crow to make the banjo cool.” Chicago Tribune. Oct. 22, 2012, https://www.chicagotribune.com/2012/10/22/it-took-an-old-crow-to-make-the-banjo-cool-2/.

[63] Id.

[64] Jacques, supra note 2.

[65] Christopher John Farley. “Music: Can 13 Million Hootie Fans Really be Wrong?” TIME. Apr. 29, 1996, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,984475-1,00.html.

[66] Id.

[67] Id.

[68] Id.

[69] Jon Caramanica. “Hootie & the Blowfish, Great American Rock Band (Yes, Really).” The New York Times. June 6, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/06/arts/music/hootie-and-the-blowfish-cracked-rear-view.html.

[70] Id.; Hank Shteamer. “Black Pop Artists Have Long Gone Country. Here’s a Brief History.” The New York Times. Marc. 21, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/21/arts/music/beyonce-black-pop-artists-country-music.html?searchResultPosition=1.

[71] Shteamer supra note 70; Matt Williams. “Darius Rucker to Release ‘True Believers’ My 21st.” Focus on the 615. Marc. 14, 2013, https://focusonthe615.com/2013/03/14/darius-rucker-to-release-true-believers-may-21st/#:~:text=Darius.

[72] Gayle Thompson. “Darius Rucker, ‘Wagon Wheel’ Cover Decided in Unlikely Place.” The Boot. Jan. 4, 2013, https://theboot.com/darius-rucker-wagon-wheel/#:~:text=Gayle%20Thompson,'re%20playing%20the%20song.%22.

[73] Id.

[74] Birnbaum, supra note 10 at 19-20.

[75] See Bob Dylan, “Highway 51” on Bob Dylan (CD, Columbia 1962).

[76] See Heylin, supra note 10 at 94; Sonny Terry, “Rock Me Mama,” https://open.spotify.com/track/3vrkBe0w8tpqW3xTsXbwTZ?si=b82fb76c3af44730.

[77] Birnbaum, supra note 10 at 111.

[78] Id.

[79] Reisman, supra note 11 at 121-122

[80] Birnbaum, supra note 10 at 4.

[81] See Melvin Jackson, “Rockin’ and Rollin’” on Rockin’ and Rollin’ Vol. 1 (1948-1950) (1951), https://open.spotify.com/album/5aIifcQg2xQpoGLAr5XjTN?highlight=spotify:track:0zlMup6ZVN5GWC2tasyhUv.

[82] See id.

[83] Id.

[84] See Birnbaum, supra note 10 at 4.

[85] See Kamin, supra note 41.

[86] Andrien v. So. Ocean Cty. Chamber of Commerce, 927 F.2d 132, 134-5 (3d Cir. 1991).

[87] Erickson v. Trinity Theatre, Inc., 13 F.3d 1061, 1068-69, 71 (7th Cir. 1994); see Moi v. Chihuly Studio, Inc., 846 F. App'x 497, 498 (9th Cir. 2021) (holding that “a ‘joint work’ requires each of the following elements: ‘(1) a copyrightable work, (2) two or more 'authors,' and (3) the authors must intend their contributions to be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.’”) (quoting Aalmuhammed v. Lee, 202 F.3d 1227, 1231 (9th Cir. 2000)).

[88] Janky v. Lake Cnty. Convention & Visitors Bureau, 576 F.3d 356, 362 (7th Cir. 2009) (“crediting another person as a co-author is strong evidence of intent to create a joint work.”).

[89] Brod v. Gen. Publ'g Grp., Inc., 32 F. App'x 231, 235 (9th Cir. 2002) (demonstrating intent of creating a joint work by listing the completion date as 1997, after both authors provided contributions, instead of 1991, the completion date of plaintiff’s contribution).

[90] See U.S. Copyright Registration PA0001233553.

[91] See U.S. Copyright Registration PA0001233553.

[92] See Bobbycast, supra note 2.